Chatbot NLU Series, Part III

Chatbot NLU Part III: Date-Time Parser

Entity extraction and evaluation is an important part of e-mail processing and chatbot NLU pipelines. In this post, we’ll see how to parse date-time strings out and evaluate them into Python objects.

Customer care and sales domain always contain date-time expressions; more appointment dates in sales context, more past ‘complaint’ dates in customer care area. Whether marking the date to the sales agent’s calendar, search for a ticket in CRM system or join as a feature to NLU algorithms; recognizing and evaluating date-time expressions is a crucial part of customer care text processing.

Can we have a phone call tomorrow afternoon, after 14.00?

I phoned yesterday at 11.00, 14:00 and 16:00 o'clocks. No answer from the customer hotline!!

Let's schedule a Skype call. I'm free on 26th March, Monday 14.00pm or 12.00pm. Would that be suitable?

In sales context, dates can vary from very near future (today afternoon) to indeed very far away future (in 6 months). In this post, we’ll process precise dates as an example; longer term dates can be parsed similarly. We will recognize and parse formal language of date-stime strings with Context Free Grammars. I like to use Lark for mainly efficiency reasons, availability of several parsing algorithms and full Unicode support. Another very important issue is Lark can handle ambiguity, as we’ll see very soon date-time grammars can get quite ambiguous. PyParsing is also great, but Lark is much lighter and faster. We’ll visit performance issues later; first we focus on forming the grammars. We’ll parse German date-time expression for an example. As you will see from the design

- Non-numeric nonterminals are language dependent i.e. date-time words morgen/morning, gestern/yesterday…

- Ways of writing date time expressions are different in these two languages. In my observation USA English contains more patterns with timezone info i.e. PST, PDT, GMT etc. My feeling is that, timezones add more ambiguity to USA English date-time grammars.

Before beginning it’s useful to have basic information on CFGs and attribute grammars. The Dragon book is an excellent reference and should be on the shelf of every compiler designer.

Enough speaking, let’s see the CFGs on action:

Designing the Grammar

We’ll build a grammar to recognize the precise dates: dates look like appointment dates, near future or near past. For instance yesterday 11 am, yesterday afternoon, tomorrow at 8.00Uhr, 23 March Monday, 12:00… Far away dates i.e. after 6 moths, in 3rd Quarter, beginning of the new year … can be processed similarly. Let’s make a list of strings that we want to recognize.

We begin with days, either weekdays or relative days yesterday, tomorrow… Let’s include their abbreviations as well. Abbreviations can end with a period or not.

Mittwoch

Freitag

Gestern

Heute

Morgen

Mi

Mi.

We can add time of the day to the above. Notice that Morgen can be either tomorrow or morning i.e. can join as a weekday or as a time of the day qualifier.

Mittwoch vormittag Wednesday afternoon

Heute nachmittag today afternoon

gestern morgen yesterday morning

Do nachmittag Thursday afternoon

morgen nachmittag tomorrow afternoon

Freitag ganzer Tag Friday all day

We can qualify the day expression with ‘next’ as well. Don’t forget to relax umlauts by non-umlaut equivalents.

Kommenden Mittwoch coming Wednesday

n[äa]chster Woche Montag next week Monday

OK, customer might also say this day or that day. I’m available Wednesday or Friday afternoon style patterns frequently occur in customer text. I’ll also discard whitespaces while compiling the grammar, time of the day words can be written together and frequently are written together. Also particles such as Uhr, h, -, / are often written next to numbers with or without spaces. It’s a good idea to discard spaces in date-time parsing in general, independent of the language.

Mi or Do. Wednesday or Thursday

heute oder am Do nachmittags today or Thursday afternoon

heute nachmittag oder Freitag morgen today afternoon or Friday morning

Donnerstag oder Freitag vormittags Thursday or Friday mornings

nachste Woche Dienstagnachmittag oder Mittwochnachmittag next week Tuesday afternoon or Wednesday afternoon

We can turn these strings into context free production rules:

precise_date → weekday_or_expr | weekday_t | weekday

weekday_or_expr → weekday_t_or_weekday_t | weekday_or_weekday

weekday_or_weekday → weekday OR weekday (time_of_day)?

weekday_t_or_weekday_t → weekday_t OR weekday_t

weekday_t → weekday time_of_day

weekday → NEXT DAY | DAY | DAY_ABBR

time_of_day → TIME_OF_DAY

DAY → "Montag" | "Dienstag" | "Mittwoch" | "Donnerstag" | "Freitag" | morgen | heute

DAY_ABBR → "Mo" | "Di" | "Mi" | "Do" | "Fri"

NEXT → \[Nn\][aä]chste[rns]? | [Kk]ommende[rn]?

OR → "oder"

TIME_OF_DAY → (vor|nach)?mittag | morgen | ganzer tag

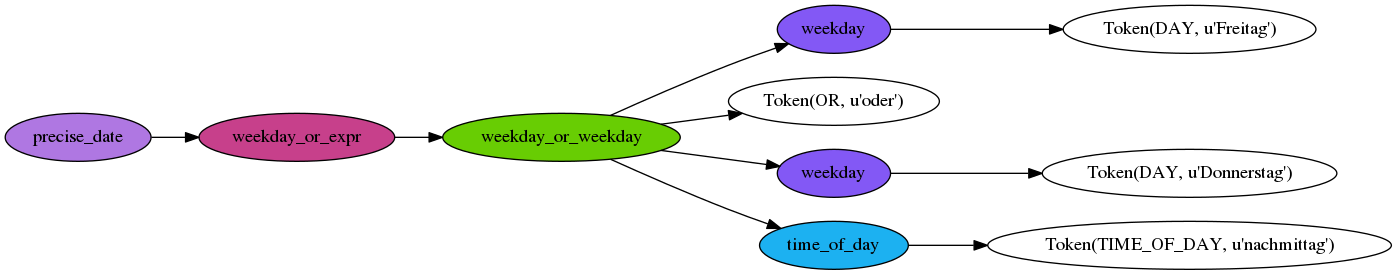

Notice the ambiguity even at this level. Ambiguity is caused by strings of the form Freitag oder Donnerstag nachmittag, current grammar parse them to weekday OR weekday (TIME_OF_DAY)?, which leads to the following parse tree:

One could take the short cut

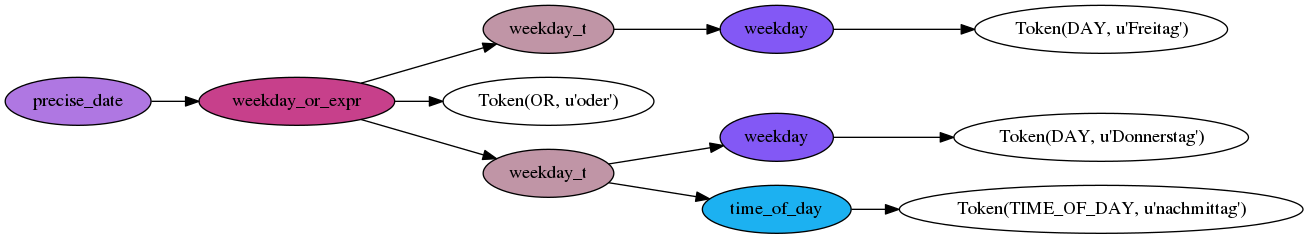

precise_date → weekday_or_expr | weekday_t

weekday_or_expr → weekday_t OR weekday_t

weekday_t → weekday time_of_day | weekday

then, Freitag oder Donnerstag nachmittag ends up with the following parse tree:

which is not what you want most probably. The string belongs to the language in both cases, however semantics are very different. In the first tree, the two weekdays and the time_of_day are at the same level. One can attach time_of_day to the both days if you traverse from the weekday_or_weekday node. In the latter, time_of_day node is sibling to only one weekday node, which happens to be Thursday. This parse tree has the meaning (Friday) or (Thursday afternoon).

If one string can end up in several parse trees, always ask yourself: ‘How should be the precedence/evaluation/semantics?’ While designing the grammar, keep the semantics in your head as well. While designing any parser, you are the king of the semantics universe. The grammars carry semantics that you charge, the generated parse trees are structured the way you want.

OK, let’s add the time strings as well. The time string business is a bit tricky, because numbers in general can be many different things, not only part of date strings. What I mean is that:

10 Uhr

10:30Uhr

10:30

10 am

zwischen 11 und 12 Uhr

zwischen 11-12Uhr

15:00-17:00Uhr

gegen ca. 15Uhr

zwischen 11 und 12 Uhr oder ab 16Uhr

vom 16 bis 17Uhr oder ab 18 Uhr

vom 16 bis 17Uhr oder zwischen 18-19Uhr

are %100 time strings, no matter how and where they occur whereas this 11:

morgen ab 11 tomorrow beginning from 11

or even ab 11 can alone without more qualifiers, mean many things other than a time without the tomorrow, which makes this expression a date-time string. For the sake of clarity, I’ll skip these sort because one needs to interleave days and numbers. Here’s a basic grammar for time strings:

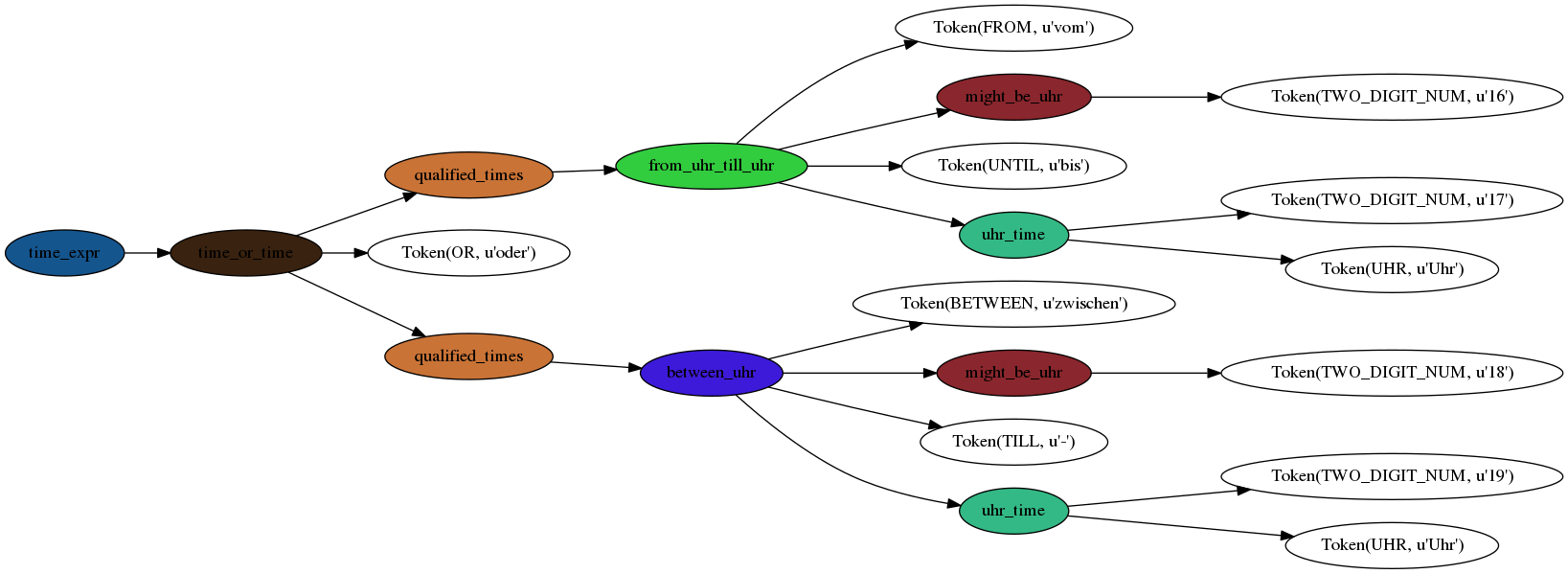

time_expr → time_or_time | qualified_times | uhr_time

time_or_time → qualified_times OR qualified_times

qualified_times → (from_uhr_till_uhr | between_uhr | qualified_uhr)

from_uhr_till_uhr → FROM (uhr_time|might_be_uhr) UNTIL uhr_time

between_uhr → (BETWEEN)? (uhr_time|might_be_uhr) (TILL|AND) uhr_time

qualified_uhr → (TOWARDS|UM|UNTIL|AB|FROM) (CIRCA)? uhr_time

uhr_time → DEF_HOUR UHR | DIGIT_NUM UHR | DEF_HOUR

might_be_uhr → TWO_DIGIT_NUM

TWO_DIGIT_NUM → \b[012]\d

DEF_HOUR → \b[012]?\d:[012345]\d?

UHR → "Uhr" | "h"

BETWEEN → "zwischen" | "zw."

AND → "und"

AT → "um"

ZUM → "zum"

AB → "ab"

TOWARDS → "gegen"

AMPM → "am" | "pm"

TILL → "-"

FROM → "von" | "vom"

UNTIL → "bis"

MAX → "max." | "max"

CIRCA → "ca." | "ca"

I parsed the string vom 16 bis 17Uhr oder zwischen 18-19Uhr as an example.

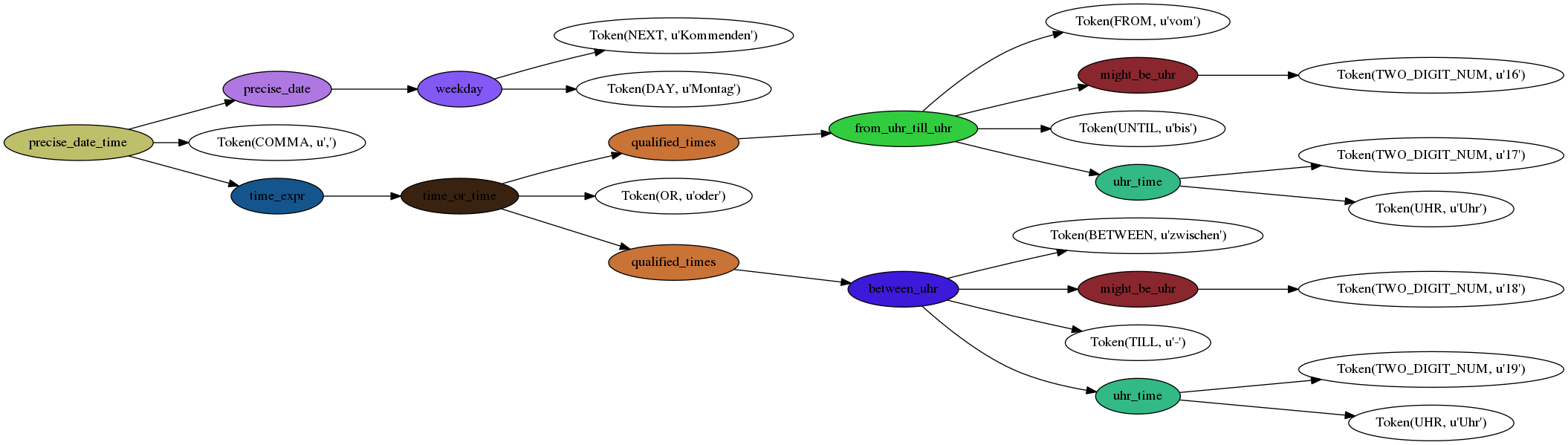

We’re ready to complete the grammar combining date and time:

S → precise_date_time

precise_date_time → precise_date time_expr | precise_date | time_expr

I’ll put together a Lark grammar, combining dates and times:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

from lark import Lark

date_grammar = u"""

precise_date_time: precise_date (COMMA)? time_expr | precise_date | time_expr

time_expr: time_or_time | qualified_times | uhr_time

time_or_time: qualified_times OR qualified_times

qualified_times: (from_uhr_till_uhr | between_uhr | qualified_uhr)

from_uhr_till_uhr: FROM (uhr_time|might_be_uhr) UNTIL uhr_time

between_uhr: (BETWEEN)? (uhr_time|might_be_uhr) (TILL|AND) uhr_time

qualified_uhr: (TOWARDS|AT|UNTIL|AB|FROM) (CIRCA)? uhr_time

precise_date: weekday_or_expr | weekday_t | weekday

weekday_or_expr: weekday_t_or_weekday_t | weekday_or_weekday

weekday_or_weekday: weekday OR weekday (time_of_day)?

weekday_t_or_weekday_t: weekday_t OR weekday_t

weekday_t: weekday time_of_day

weekday: NEXT DAY | DAY | DAY_ABBR

time_of_day: TIME_OF_DAY

uhr_time: DEF_HOUR UHR | TWO_DIGIT_NUM UHR | DEF_HOUR

might_be_uhr: TWO_DIGIT_NUM

DEF_HOUR: TWO_DIGIT_NUM ":" TWO_DIGIT_NUM

TWO_DIGIT_NUM: DIGIT DIGIT?

DAY: "Montag" | "Dienstag" | "Mittwoch" | "Donnerstag" | "Freitag" | "morgen" | "heute"

DAY_ABBR: "Mo" | "Di" | "Mi" | "Do" | "Fri"

NEXT: "Nächster" | "Nächsten" | "Nächste" | "nächster" | "nächsten" | "nächste" | "Kommenden" | "Kommender" | "Kommende" | "kommenden" | "kommender" | "kommende"

TIME_OF_DAY: "vormittag" | "nachmittag" | "mittag" | "morgen" | "ganzer tag"

COMMA: "," | ";"

UHR: "Uhr" | "h"

BETWEEN: "zwischen" | "zw."

AND: "und"

AT: "um"

ZUM:"zum"

AB: "ab"

TOWARDS: "gegen"

AMPM: "am" | "pm"

TILL: "-"

FROM: "von" | "vom"

UNTIL: "bis"

MAX: "max." | "max"

CIRCA: "ca." | "ca"

OR: "oder"

%import common.WS

%import common.DIGIT

%ignore WS

"""

parser = Lark(date_grammar, parser="lalr", start="precise_date_time")

text = u"Kommenden Montag, vom 16 bis 17Uhr oder zwischen 18-19Uhr"

parse_tree = parser.parse(text)

print parse_tree

and parsed the string Kommenden Montag, vom 16 bis 17Uhr oder zwischen 18-19Uhr:

More of the Parsing

Earlier, I spoke about the Bible of the compiler writing:), the Dragon book. The Dragon book, or any compiler design book contains parsing algorithms, classes of languages that can be parsed with these algorithms and efficiency issues. In this section we’ll see LR, SLR , LALR and Earley parsers. First we again have a look at bottom-up and top-down parsing.

Top-down parsers begin with grammar rules and try to reach the input string. Left recursive grammars cannot be parsed by recursive descent style top-down parsers. In general, recursive descent top-down parsers backtrack a lot with ambigious grammars.

Bottom-up parsers begin with the input string and try to reach the starting symbol, building the parse tree from the input. Though procedure looks very similar, indeed bottom-up parsing is much more powerful than top-down parsing. Many modern compilers use bottom-up parsing only.

Bottom-up parsing is usually done by shift-reduce parsers and shift reduce parsers avoid backtracking at all. Recursive descent parsers has the problem of reparsing the subtrees, bottom-up parsing avoids this problem via holding the current state by holding a stack and production rules together.

The convention is:

- an LR(k) grammar is one that can be parsed bottom-up with k tokens of lookahead and an LR(k) language one that is produced by an LR(k) grammar;

- an LL(k) grammar is one that can be parsed top-down with k tokens of lookahead and, again an LL(k) language is produced from a such corresponding grammar.

- LL(k) ⊂ LR(k) for any k, and LL ⊂ LR.

Earley parser is a dynamic programming algorithm that implements top-down parsing efficiently by avoiding reparsing the subtrees over and over. The dynamic programming table holds a list of states that represent the partial parse trees. By the end of the string, the table compactly encodes all the possible parses of the input string. This way, each subtree is parsed only once and shared by all the relevant parses. The parses forest is hold in a very elegant data structure called shared forest. Generalized LR Parsing is a great resource for learning more about data structures for encoding the parsing information as well as LR parsing in general.

LR parsers are shift-reduce parsers, so a type of bottom-up parsers. LR(k) parsers have a “configuration” correspond to each state in order to determine to shift or to reduce. A “configuration” is a set with the information of: 1. Where the parser is so far with the production rule 2. The lookahead, what tokens to expect after the production rule is completed.

SLR and LALR parsers are common variants of LR parsers SLR is implemented with a small parse table and a relatively simple parser generator algorithm, comparing to LALR. Both SLR and LALR implementtions have no backtracking. LALR parsers are used more commonly in compiler writing than the other types, though they are less powerful than LR(1), one rarely needs all power of LR(1). yacc and many other compiler compilers has default parser LALR. LR(1) parsers are really big, I mean exponentially bigger than LALR(1). Hence:

- LR(0) ⊂ SLR(1) ⊂ LALR(1) ⊂ LR(1)

- SLR(1) is fairly a weak parsing method method comparing to LALR(1). LALR(1) parsers are more specific while resolving the conflicts that arise during parsing, basically when to shift or reduce.

Our tiny grammar is LALR(1). It has ambiguities that you can avoid by a 1-token lookahead, but it’s a bit too ambigious to be LR(0).

Lark library implements both Earley and LALR parsers. Earley algorithm has worst case time complexity O(n^3), while LALR(1) has linear complexity. One of the things that I like about Lark is that, it implements a very common algorithm LALR, but also a very powerful one, Earley. Our grammar is not bad:), not very far away from a full recognizer; but a real world date-time grammar is much more ambigious(believe my word here, if I post here parsing table of the grammar that I’m using for e-mail processing you get into shock:)). When one has both Earley and LALR, one can parse almost everything.

Language Modelling

OK, we parse out date-time strings to look for a ticket in the CRM in a specific time window, or mark an appointment to the sales agent’s calendar. There’s one more catch here, you can help your statistical algorithm. Character level RNNs surely can recognize the date expressions, however you need an enormous amount of training data to distinguish dates from other numerical expressions. Why not to replace date-times with several tokens, according to their types:

I phoned yesterday afternoon. I phoned past_date_tok.

Can we schedule a call for 5th April, Fri 17.00-18.00 or 19.00-20.00? Can we schedule a call for close_date_tok?

I'm available tomorrow afternoon 17.00. I'm availble close_date_tok.

Are you available tomorrow afternoon, after 17.00? Are you available close_date_tok?

Go one step further and remove the stopwords to have raw forms:

phoned, past_date_tok

schedule, call, close_date_tok

available, close_date_tok

available, close_date_tok, ?

What is the semantical difference between 3rd and 4th sentence if you want to classify class of e-mails that contains potential customers? Basically, nothing. Sentence 1 rather looks like a complaint, with a past date reference. Raw forms reflect a very compactified form, your model won’t suffer from data sparsity; date parsing really compactifies the corpus. Even a vanilla SGD can perform very good with this training set.

I prepared a tiny corpus to form a LM with SRILM:

Let's schedule a call tomorrow morning.

Let's schedule a call tomorrow, after 17.00 pm .

Let's schedule a call on Wednesday morning 10.00 am.

Let's schedule a call for Thursday morning.

Let's schedule a call tomorrow afternoon.

Let's schedule a call on Tuesday afternoon.

I'm available tomorrow afternoon, after 17.00 o'clock.

I'm available for a phone call by next week Monday.

Are you available for a phone call Tuesday, 21th April?

We can schedule a phone call on 22th March, Wednesday.

What is your availability for 24th March, Friday?

I'm available tomorrow, between 15.00-17.00.

Are you available for a phone call tomorrow?

Are you available for a phone call next week Friday?

Are you available for a phone con Friday morning?

Are you available for a phone call on 5th March Wed, 12.00 pm CET?

Are you available for a Skype call on 6th March, 10.00 am CET?

I'd like to make a phone call next week.

I'd like to make a phone call next Tuesday, 23rd.

I'd like to make a phone call in 3 days.

I'd like to make a phone call oncoming week, Friday.

I'd like to make a phone call tomorrow afternnon.

I'd like to make a phone call tomorrow morning.

We can have a Skype call next week Tuesday, I'm available all day.

We can have a call at Friday afternoon.

We can have a call at Wednesday afternoon.

We can have a call Monday 23rd, 12.00-14.00 pm.

We can have a call at Thursday morning.

We can have a call at Monday afternoon.

We can have a call next week.

I prepared a tiny LM form the corpus above, without date-time tokenization. I couldn’t apply Kneser-Ney smoothing to discount LM as corpus is too small and order of ngrams is 3:

ngram-count -kndiscount -interpolate -order 3 -vocab -text small.txt -lm small.lm

The resulting ARPA format LM file is 159 lines long. Here are some lines from it:

\data\

ngram 1=53

ngram 2=99

ngram 3=14

\1-grams:

-1.926857 10.00 -0.004375084

-2.227887 12.00 -0.177858

-2.227887 12.00-14.00 -0.177858

-2.227887 15.00-17.00 -0.1007647

-2.227887 17.00 -0.1830591

-2.227887 17:00 -0.177858

-2.227887 21th -0.1830591

-2.227887 22th -0.1752338

-1.926857 23rd -0.09762894

-2.227887 24th -0.1752338

-2.227887 3 -0.1830591

-2.227887 5th -0.1752338

-2.227887 6th -0.1752338

-1.750765 monday -0.07502116

-1.528917 friday 0.01762764

-1.926857 thursday 0.003497539

-1.750765 wednesday -0.06495982

-1.625827 tuesday -0.159147

-1.157608 friday afternoon

-0.9357591 wednesday morning

This LM doesn’t capture semantics of the days of the week. Monday, Tuesday, Friday… admits different probabilities, where most probably it’s not what you want. All strings semantically from the same class: days of the week and should admit the same probability. Also too much probability mass went to numbers. One more step, Friday afternoon and Wednesday morning also should admit the same probability, semantically theres no difference at all. The tokenized LM is much more compact and capture the patterns:

\data\

ngram 1=9

ngram 2=13

ngram 3=8

\1-grams:

-0.5854607 </s>

-99 <s> -1.383722

-2.187521 ? -0.1704141

-2.187521 availability -0.1704141

-0.5964561 call -1.471444

-0.5854607 close_date_tok -1.478341

-0.8073095 phone -1.271117

-1.886491 schedule -0.6253927

-1.342423 skype -0.9145698

\2-grams:

-1.662758 <s> availability

-0.7596679 <s> call 0.6478174

-0.3203351 <s> phone 0.03621221

-1.060698 <s> schedule 0

-0.6627578 <s> skype -0.6118199

-0.30103 ? </s>

-0.30103 availability close_date_tok

-0.01099538 call close_date_tok -0.2903061

-0.02171925 close_date_tok </s>

-1.612784 close_date_tok ?

-0.01772877 phone call 0.2041199

-0.09691001 schedule phone 0.69897

-0.04139268 skype call -0.05115259

\3-grams:

-0.05115252 <s> call close_date_tok

-0.01772877 phone call close_date_tok

-0.009759837 skype call close_date_tok

-0.01099538 call close_date_tok </s>

-0.01930515 <s> phone call

-0.09691001 schedule phone call

-0.09691001 <s> schedule phone

-0.009759837 <s> skype call

\end\

with only 43 lines. This compacted LM will answer even to the simplest statistical algorithm as I remarked previously, now you see with your own eyes.

The semantics has never been a simple issue, it’s complicated and it’ll stay complicated. In this post, we began with parsing algorithms and travelled until to the statistical side of the semantics. I hope you enjoyed the journey. Stay tuned and have a happy Easter!